Decreasing Population in Japan and the long term consequences

The changing demographic time-bomb and rural flight means the countryside is aging, and thinning out, while the cities are ever more crowded. “When Japan” takes a look at the data and asks where is Japan going with this?

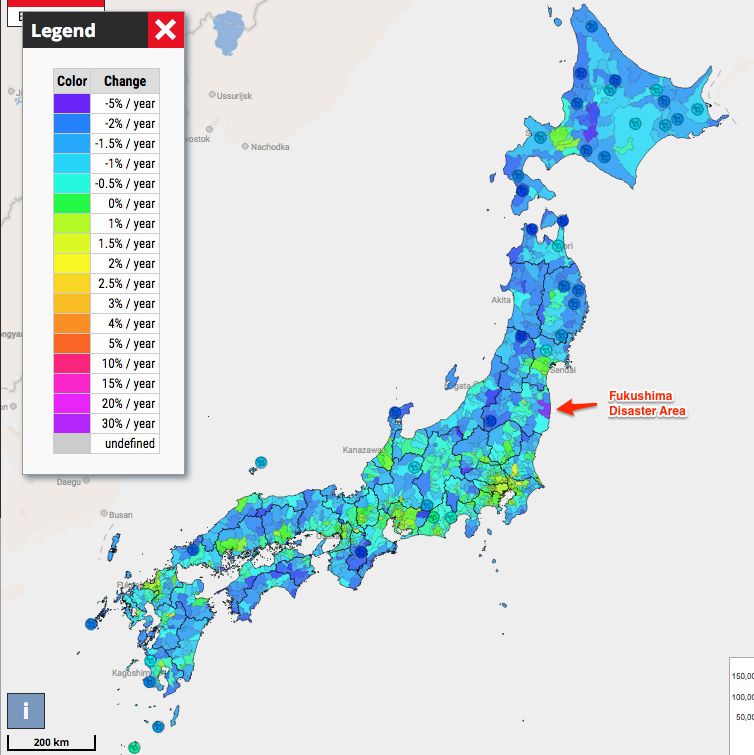

The population charts from the most recently available data hint at a bleak future for Japan. Looking at data taken from the fantastic citypopulation.de website the trend is clear with most rural populations decreasing by 1-3% a year while urban areas increase by up to 1% per year. In addition to the sobering purple area reflecting the evacuation zone from the 2011 Tsunami and Fukushima Incident, the general trends are also cause for concern.

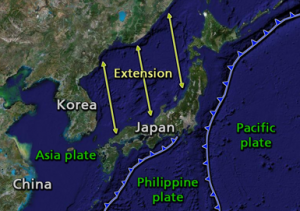

Causes of a decreasing population

While Japan often gets all the press when it comes to birthrates it is part of a general trend affecting South-East Asia whereby once the GDP goes above a certain point birthrates drop below 2 and continue as low as 1.2 for places like Taiwan and Singapore. Check the excellent ourworlddata.org article of fertility rates. The causes are many and Japan has it’s own laundry list of reasons such as, marriage rates declining, low savings rate and long working hours, cost of raising a child (link) and the practicalities of housing 2 children in a small apartment in Tokyo (link). In one study women when women were asked why they had less children than planned, the answers are overwhelmingly related to health and money. In another study that simply asked why 100 women didn’t want children, the biggest factors were “lack of free time” and “unsure they were suited (unable or dislike of children)”.

Government programs meant to counter this trend focus on making it cheaper to have children, ignoring the fact that the trends are the same in Europe where giving birth is free and early childhood is heavily subsidized (link). While Japan is extreme in how little living space there is, after the Second World War during the “baby boom” area, families packed 3-4 children into small houses and apartments without complaints. The real reason for the disinterest in having children is probably a confluence of reasons that no government policy is going to overcome without relying (however unintentionally) on immigration, as America and the United Kingdom do (link).

The culture of Japan is especially focused on women being the caregivers and men working to pay the bills. Women in their 30s are seen as washed up and often cannot progress in their careers because they are expected to leave to have children, so are never given opportunities. Even with this extreme pressure, birthrates are still one of the lowest in the world and on-par with Europe, where attitudes could not be different regarding women and men’s roles in the family (link).

It is my guess that while the pressure in Japan is particularly high for women to have children, when they do, 1 is enough due to economic and space pressures. The reality is that 1 child is probably enough to satisfy any desire a couple may have for children. Are people happier with 2 children, compared to 1? Why have 2 when the economics and practicalities makes it harder. Combine that with a younger generation that is postponing marriage and having children in their 20s, but find dating and settling down once in their 30s difficult. One of the remaining truths in Japan is that you can’t have children until you are married. With men wanting to get married in their early 30s, but wanting a partner at least 5 years younger, once women get past their 30s marriage becomes more difficult (and hence so is having children). No amount of government policy is going to fix that.

Consequences of a population change

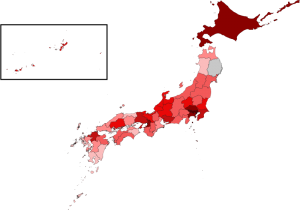

A decreasing population by definition means an aging population, as the lack of births producing a demographic graph that packs high towards the over 65s (over 30% by 2050 including a decrease in total population of 18 million). Many rural areas are already well past 30% (select the over 65 option on the map).

Links provided by the excellent populationpyramid.net and citypopulation.de.

Increase in abandoned housing

Houses with no-one living have become increasing common even in more urban areas. While there are tax reasons complicating the issue, and Japan has always had a cultural slant towards building new houses rather than buying old ones (old houses built before 1970 are not up to strict earthquake codes for example), the stark fact is that there are 1.16 houses for every household (and this has been increasing over the years).

Oversupply leads to households in more rural areas unable to sell because there are simply not enough jobs to support the numbers of people. Rural flight is a major problem as the young move to the cities for work (and the lifestyle), which increases the cost of living in the cities. Commuting time and overcrowding in Tokyo is already a problem and unless you want to live in a box, owning a home and commuting into Tokyo will require even longer train journeys in the future, which many are not willing to do.

Tourism and immigration

Over the last 15 years tourism in Japan has increased significantly (link), causing a certain amount of cultural friction as a nation that prides itself on following rules and keeping everything in order has to start dealing with the unruly masses from foreign lands (search for Kyoto Graffiti for examples, the damage to bamboo trees causing the most outrage). This is to a certain extent unavoidable (and should be expected with increased tourist – look at the Cologne Cathedral for a prime example). If you want tourist money, coping with the worst tourist will become a full time job.

How this relates to immigration is more complicated. Japan has always been weary of foreigners as the way of life in Japan is often a stark contrast to that of other countries. Unless you are able to integrate both culturally and linguistically the Japanese will find it very difficult to relax around you. So-called “half”, children with mixed heritage, can still be treated like foreigners, especially if they don’t look Asian. The Japanese attitude to foreigners is still very much full of contradictions and outdated thinking. For example, English is still considered the holy grail of international relations even thou the % of English speakers living and traveling in Japan is a small fraction of that of Chinese and Korean. A good place to start on the rough edges of Japanese attitudes to immigration it is best to go to Debito.org and read up there. “When Japan” will also post a blog post on the subject soon.

The bottom line is that immigration is not considered the solution to the aging population, although it is being used as a stop gap measure for care homes and convenience stores (the number of foreigners working at local 7-Elevens in Japan has reached close to 100% in urban areas).

Pension time-bomb and job security

With the number of older people increasing and the number of young people decreasing, pensions and the partially socialized health system are coming under increased strain. While those with a company pension from a large corporation are generally OK (pension contributions are generally 10% of your salary with a further 10% paid by the company, plus investment options) those having to make do with the standard state pension struggle to make ends meet. Health care in Japan is also a major issue, as people live longer but end up in poor health and in need of support for the last 8-10 years. While the foreign news reported with a certain amount of whimsy the fact that more adult diapers than baby diapers are being produced in Japan, the burden of elderly care on the young is clear – higher health insurance premiums and lower pensions payouts.

Not all doom and gloom?

With all the free space in Japan now due to the declining population and rural flight, the cost of living in the countryside will only decrease. If your job only involves coming into the office once a week or less, or is totally based online, then living cheap in the countryside may be a great lifestyle. Internet banking finally took off in Japan the last few years and Amazon and Rakuten are also being used increasing for items you might not find in the local supermarket. Of course, Japan is still very much a “come into the office at 9am” culture, with working from home still unpopular with large companies with a traditional Japanese work ethic. Local subway lines in Tokyo such as the notoriously overcrowded Tozai Line have experimented with campaigns to encourage flexible working hours. However, as is typical for Japan, the conditions were unnecessarily complicated for the rewards offered, so it is unlikely to have been a success in lowering commuting numbers at peak times. For the Japanese “flexible working hours” means coming in early and but leaving at the usual time, which is just overtime but in the morning.

The future for Japan?

It is almost certain that from a macro political strategy, Japan is banking on riding out the storm with as little immigration and change as possible, instead hoping on technological advances (robotics and AI) to help care for its aging population. Japan could then slowly take the foot off the gas pedal and shorten those working days, move out of the big cities, and pivot back to the kind of lifestyle enjoyed by the Samurai during the 1800s, where they hung up their swords and instead focused on the arts, humanities and generally improving themselves.